"An ecumenism of hate" is how an influential Jesuit magazine describes the apocalyptic world view fostering hatred, fear, and intolerance that unites certain fundamentalist evangelicals and "militant" Catholics. Islamic fundamentalists, jihadists, and others might also be added to these hate-filled groups.

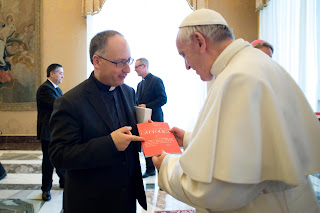

La Civilta Cattolica, a Jesuit journal, appeared in the mid-July/August edition and released online on July 13. The article was reviewed by the Vatican before publication, as is normal. It was written by the journal's editor, Jesuit Father Antonio Spadaro, and Marcelo Figueroa, a Presbyterian, who is the director of the Argentine edition of the Vatican newspaper, L'Osservatore Romano.

The title was "Evangelical Fundamentalism and Catholic Integralism: A surprising ecumenism." The article, among other things, examines how this world view has influenced US culture and politics. It points especially at the administration of President Donald Trump.

One feature of this "ecumenism of hate," according to the article, is a clear "Manichean" delineation between absolute good and evil and a confident sense of who belongs in which camp. Here it cites President George W. Bush's list of nations in an "axis of evil" and President Trump's fight against a wider, generic body of those who are "bad" or even "very bad."

The authors briefly examine the origins and spread of evangelical fundamentalist thought and influence in the United States and how many groups or movements became targeted by them as a threat to "the American way of life" and then demonized. In the past, communism and feminism were perceived as the enemy; today, "migrants and Muslims" are the targets.

The article foresees a constant conflict, culminating in a final battle, between good and evil, between God and Satan. Biblical support for this conflict is found in the Old Testament accounts of conquering and defending the promised land and ignores Jesus' love in the Gospels.

The article even makes brief mention of the theological-political vision of Rousas John Rushdoony, a founder of "Christian Reconstructionism," which calls for a nation built on Christian ideals and strict laws drawn from the Bible. This "Dominionist" doctrine, it claims, has inspired groups and networks like the Council for National Policy, as well as the White House chief strategist, Steve Bannon, with his "apocalyptic" world view.

However, a theocracy with the state subjected to the Bible, the article explains, uses a rationale that is similar to that of Islamic fundamentalism. "At heart, the narrative of terror" that feeds the jihadist imagination and the neo-crusaders draw from wellsprings "that are not too far apart."

According to the authors, "a strange form of surprising ecumenism is developing between evangelical fundamentalist and Catholic integralists" as they appeal to similar fundamentalist values and have "the same desire for religious influence in the political sphere."

Evangelicals and Catholics share similar values and goals when it comes to abortion, same-sex marriage, religious education in schools, and other moral issues. Both "condemn traditional ecumenism and yet promote an ecumenism of conflict that unites them in the nostalgic dream of a theocratic-type state."

"Triumphalist, arrogant and vindictive ethnicism is actually the opposite of Christianity," they warn.

The most "dangerous" feature of this "strange ecumenism" between Catholic and evangelical fundamentalists is the xenophobia and Islamophobia that promotes "walls and purifying deportations" they add.

The authors explain that these abuses in fundamentalism, as well as confusing spiritual power with temporal power, are some of the reasons why Pope Francis is "so committed to working against 'walls' and any type of 'war of religion.'" Religion must be put "at the service of all men and women. Religions cannot consider some people as sworn enemies nor others as eternal friends."

"Today, more than ever, power needs to be removed from its faded confessional dress, from its armor, its rusty breastplate," the article notes. A "truly Christian" theological-political plan looks to the future and "orients current history toward the kingdom of God, a kingdom of justice and peace"; it fosters "a process of integration that unfolds with a diplomacy that crowns no one as a 'man of Providence.'"

The article concludes by warning that the temptation to build a false alliance between politics and religious fundamentalism is built on a fear of chaos and the breakdown of established order. That fear can be manipulated when politics increase the tenor of conflict, exaggerate the potential disorder and make people upset by painting "worrying scenarios" that have nothing to do with reality.

Religion is then used as a way to guarantee order, and a political platform comes to exemplify what would be required to get there, the authors explain. "Fundamentalism thereby shows itself not to be the product of a religious experience but a poor and abusive perversion of it," That is why Pope Francis upholds a narrative counter to "the narrative of fear" because "there is a need to fight against the manipulation of this season of anxiety and insecurity."

The pope, the authors conclude, courageously offers "no theological-political legitimacy to terrorists, avoiding any reduction of Islam to Islamic terrorism. Nor does he give it to those who postulate and want a 'holy war' or to build barrier-fences crowned with barbed wire." The only barbed wire for a Christian "is the one with thorns that Christ wore on high."

This article has been criticized by many, especially conservative Catholics. Their criticism is directed in particular at the perceived ignorance of the authors of American politics and their supposed liberalism. Whether this is true or not is beyond the scope of this post. What is noteworthy is that the Vatican gave this article its imprimatur.

That alone is enough to irk these conservatives who despise Francis. He, and many influential figures at the Vatican today, they assert, want to move away from traditional Catholic teachings, and form a new alliance with modernity. It is clear why these conservatives oppose this article. so vigorously.

What intrigues me in this article is the idea of an "ecumenism of hate." Ecumenism, as it commonly understood, is based on love. Love for those who are different; love for those whose theology may contrast sharply with our own, but who nevertheless are part of the Body of Christ because the Body by its very nature consists of many parts, each of which is necessary for the proper functioning of the whole.

The authors perceptively have noted how an ecumenical unity of sorts can be built on hatred for others and an intolerance for them and their beliefs. Such an ecumenical unity of hatred shares a world view that is not limited only to Christians of various fundamentalistic stripes but also to other fundamentalists, whether Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish or Muslim.

All these types of fundamentalism are founded on a hatred of others that often expresses itself in violence. Intolerance breeds a contempt that is not afraid to resort to violence. The goal, ultimately, is to destroy the other. That, of course, is the antithesis of love. Fundamentalism is rooted in hatred.

Fundamentalism is also Manichaean. It is a dualistic belief that there is a good/ spiritual world that is in constant conflict with an evil/ material one. The good world is associated with light, while the evil world is associated with darkness. In such a world view everything is either good or evil, white or black, positive or negative. There is nothing in between.

Theirs is a binary world in which everything is reduced to its basic simplicity. Then there are no grays, but only white or black. In that world, thinking is unnecessary, since everything is clearly right or wrong. Sacred books are interpreted literally or, if that is not possible, are manipulated to say whatever has already been determined to be correct. There is no room here for any ambiguity. Small wonder that so many are attracted to it, blindly follow leaders, such as Trump, and are even willing to die, if need be, for their cause.

Not all who appeal to the fundamentals of a belief system are fundamentalists of the type portrayed in this article. But many fundamentalists are motivated by hatred, even if they do not realize it. Some (maybe, many) evangelical Christians and Catholics have hated each other for centuries. However, they have not always been aware of the common ground they shared and continue to share on contentious issues such as abortion and same-sex marriage. There are, indeed, many more issues on which they are united.

To call this an "ecumenism of hate," as the authors of this article do may sound "preposterous" to their critics, yet there is a ring of truth to it. Spadaro and Figueroa have put their fingers on some of the common elements that unite various expressions of fundamentalism in many different religions. This includes ISIS. Widespread Islamophobia does not mean that there is no common ground even with this extreme form of Islam.

The critics blame the authors for gross inaccuracy and the use of extreme language, but even the whole industry of critics that sprouted up in the days immediately following publication of the article has not been sufficient to disprove the thesis of the authors about an ecumenism of hate that unites these fundamentalisms.

"An ecumenism of hate" is indeed a special ecumenism that deserves our careful consideration. One does not have to agree entirely with the authors in order reflect on this new type of ecumenism, one that is based on common elements, but these elements are rooted in hatred rather than love, as in traditional understandings of ecumenism.